Serving ice cream to sunburned young families was the first job that Tyson Millner lost to a machine. It was shaped like a fat, upright lobster, and had five arms. It was there one morning behind the counter, illuminated by a special track light, when he showed up for his shift. Mrs. Huggard, his boss, the shop’s owner, called it “Lenny” after a character in a book she loved. It had some remarkable abilities. It could guess people’s orders before they placed them based on what they’d ordered in the past and was programmed to tease them with corny quips. If a girl liked pecans on her sundaes, it might say, retrieving her name from its perfect memory, “You’re nuts for nuts, Luanne!” Or, if she wanted bananas, “You’ve gone bananas!” These wisecracks never failed to bring on squeals, even from children who’d heard them many times. Also thrilling to them was Lenny’s physical manner, which was that of an overburdened juggler continually on the verge of flubbing up. Simulating rising panic, its articulated, claw-tipped arms would speed up crazily, threatening disaster, as they dispensed candy sprinkles and caramel sauce, blended milk shakes and built top-heavy cones that it pretended were too tall to hold and yet, despite much mock bobbling, never dropped.

Tyson, too, found Lenny charming—at first. They were partners, the way he saw it, a comic duo. He helped with tasks that Lenny couldn’t manage, such as clearing clogged syrup spouts, handling paper money (Lenny could only process cards), and topping off sundaes with a glossy cherry perched on a frilly squirt of canned whipped cream. This cherry business, with Tyson at the ready, suspending the piece of fruit above the bowl as fake-fumbling Lenny assembled the confection, grew into their most popular routine. Another act that delighted the little ones consisted of Tyson standing at Lenny’s “shoulder,” watching his movements and wielding a small wrench as though prepared to swoop in and readjust him, or maybe deactivate him, should he screw up. But Lenny never screwed up. In fact, he kept improving, endowed by his manufacturer with the ability to observe and refine his own behavior. Someday he might even learn to place a cherry, dimpling it into the cream so it stayed put.

Within a few weeks of Lenny’s installation, traffic at the shop had nearly doubled, and Tyson decided to ask a second time for the raise he’d been expecting. His wage, he’d understood when he was hired, was preliminary, probationary, and supposed to go up automatically after a month or two. When this didn’t happen, Tyson started grouching about unforeseen expenses in his life, from the need to replace the bald tires on his truck to a surge in the price of Clarifex, a drug that calmed his raging acne. Mrs. Huggard responded with grumbles of her own. A pack rat had died in a drainpipe in the wall of the apartment building she owned next door, causing a leak that soaked into the Sheetrock and spawned a bloom of toxic mold. She had to hire a licensed abatement firm at $150 an hour. But even worse, she let him know, tourism was down throughout the region thanks to hysterical media reports concerning a rare but deadly tick-borne virus local to southern Utah’s red rock hills. Sensitive to her troubles, Tyson backed off, but when Lenny appeared and worked his miracle, attracting new customers from throughout the area even as fall approached and the weather cooled, he decided his demands were not unreasonable.

He approached his boss in her office behind the shop at the end of a Thursday, the day she did her books. Surrounded by her collection of witty mugs—Same Old Shit, Different Day; The Best Man for the Job is Usually a Woman, etc.—she was filling out a spreadsheet on her computer. Mrs. Huggard had a bitter streak. The rumor was she’d been the longtime mistress of a married U.S. congressman who’d found religion during a close election and bought her silence with a large lump sum that she’d used to start the shop. To Tyson, she looked like a loving soul defeated, a merry spirit curdled by worldly hurts. Her gray-green eyes were permanently narrowed and her hair was a perfect blond fury, set and sprayed, rigid enough to cage a little bird. She lived in the top rear unit of her building, where Tyson had once helped a mover deliver a dryer. Her furniture was brown leather, like a man’s, and through the open doorway of her bedroom he’d glimpsed an old poster of a movie cowboy blasting away with a lever-action rifle. The only touch of softness in the place was an odd little altar on a window seat consisting of candles and amethysts and sage leaves arranged in a crescent around a bright gold coin. “Prosperity magic," she’d answered when he’d asked. “The sun streams in and activates a vortex.”

Tyson stood by her desk and made his pitch while she leaned back in her new hydraulic chair, her elbows resting on its arms and her fingertips in a steeple under her chin. He reminded her of the promises she had made when she hired him off an online bulletin board maintained by a state-run service for at-risk teens. Youth Horizons—a boot-camp like program in the desert that he’d been sentenced to by a lady judge after calling in a bomb threat to his school on a day when he couldn’t bear for his friends to see the volcanic pimples on his face—was the cruelest summer of his life. On the very first night a camp-mate snatched his Ritalin, forcing him to undergo withdrawal while enduring a cycle of freezing predawn showers, barefoot five-mile runs, marathon computer-coding classes, and trust-building leaps from a tower behind the barracks into other campers’ outstretched arms. The counselors told them the idea was to break them down and then rebuild them, but the program ended before phase two was done.

“You told me you’d bump me up after a month,” he said. “I just had to prove to you I didn’t steal. Well, I didn’t. I haven’t.”

“You’re reformed.”

“I’m honest and punctual, is what I am.”

“Not to mention immaculately groomed.”

Tyson’s right hand floated up and touched his forehead, a reflex when someone mentioned his appearance.

“Don’t pick,” she said. “It won’t heal if you keep picking. And that would be a shame, because you’re handsome. Fundamentally. Under all the rough stuff.”

Tyson had been consoled this way before, mostly by church girls, those experts at snarky praise. Their compliments, if you took them in, settled into your system like spoiled food, producing pangs and churns and aches. It was better to be called ugly and bleed cleanly. That could be bandaged, dealt with by first aid.

Tyson pressed ahead. In case Mrs. Huggard hadn’t listened last time, he described his circumstances to her. His landlord—his aunt—was on mobile dialysis, with no other income besides the rent he paid her. As a good Mormon, one tenth of his income went to the Church. Most important, though, he was the sole responsible male in the life of a young single mother, his cousin Kylee, whose three-year-old son had developmental challenges that called for psychological checkups in Salt Lake City and kept her from working outside the home. He didn’t support his cousin—she got church welfare—but his occasional loans and gifts bridged her worst shortfalls and wardrobe needs, letting her focus on being a good mom.

“That’s deeply stirring,” Mrs. Huggard said, “but your pay should reflect your performance, not your problems. The truth is, it’s Lenny who deserves a raise.”

“He can’t even put cherries on,” said Tyson.

“Maybe we don’t need cherries. Do people eat them?”

“They’re the finishing touch. They’re traditional.”

“They’re wasteful. Nobody eats them. I see them in the trash.”

“They’re expected,” said Tyson.

“They’re barbershop quartets. Used to seem cheerful. No one quite knows why.”

Before Tyson could argue his point further, Mrs. Huggard cut his schedule. She informed him that the shop would be closed on Mondays so that Lenny could be serviced, tuned, and cleaned by the company she leased him from. She suggested that Tyson, if he were “future positive,” might want to learn to perform such work himself. She offered to ask the company’s mobile tech team, which was based in Las Vegas and worked out of a van equipped with costly electronic tools, to let him stop in and observe its work on Mondays. He could think of it as an unpaid internship.

“I don’t think so. No interest,” said Tyson. He loathed computers. He even disliked his phone. Youth Horizons had drilled him in a gospel of tripling and quadrupling opportunities for anyone able to size a digital photo, or group all his passwords under one super-password, but then why were the people who taught these skills so grim? Why were they herding delinquents through the desert, not cruising eight miles above it wearing headphones? And this was the sick part: According to one counselor, the day was approaching when most computer work would be performed by other computers. Then what? It’s why when Kylee felt all cooped up that one time and begged him to pay for an online graphic design course, he bought her a stationary bike instead.

“I ought to go back and close up and clear the till,” he said. “I left him alone in there.”

Mrs. Huggard raised an index finger as if inviting him to witness something. She swiveled around in her chair and tapped her keyboard, calling up a screen on her big desktop that showed a split view from the security cameras: the front door on the right, the counter on the left. The door had been shut, its latching cross-bar lowered, and its one-way reflective sun curtain pulled down. But that was not the sight that startled Tyson. Standing at the counter near the cash drawer and casting a crisp dark shadow on the white tiles, Lenny was rapidly counting the day’s take and stacking the bills and coins with all five claws.

“You know how he mastered that?” Mrs. Huggard said.

Tyson didn’t, and wasn’t about to guess.

“By patient observation. By watching you.”

He fasted on Sunday. He fasted once a month on the schedule set down by the Church, the chief source of structure in his life since Youth Horizons had broken him down and only partially rebuilt him. His Mormon faith confused him for the most part, particularly its ideas about the afterlife, when risen souls would inherit their own planets and reign over them as God reigns over ours. But there was one doctrine that made sense to him: preexistence. Before we were born, according to this teaching, we chose our future lives—from the people who would become our friends and families, to the most crucial challenges we’d face. That’s why no problems on earth were insurmountable; we’d already solved them in our prior state. The trick was retrieving these answers through the veil, which was where fasting came in. It quickened thought.

Like most businesses in Cedar City, the ice cream shop was closed on Sundays, but Tyson felt prompted to drive there after church on his way to Kylee’s place, where he’d promised to watch his nephew while she cleaned. He parked his truck across the street and watched the sunshine baste the wide front window. He pictured Lenny locked in the backroom, shrouded in the bluish plastic sheet that shielded him from dust. Tyson wished he could spend some time alone with him, if only so they could banter about nothing using the goofy scripts in Lenny’s memory. “Oh fudge, we’re out of chocolate.” Or: “Willya grab some vanilla from the chilla?” At work, with Mrs. Huggard spying on them through the security portal on her desktop, they only pretended to have fun, but underneath the mood was pressured, intense. It led to mistakes, at least on Tyson’s part. Just yesterday he’d dumped a tall parfait that Lenny had spent five minutes layering, bringing tears to the eyes of a patient birthday girl, who turned to her father and wailed, “My special treat!” Lenny promptly started a new parfait, but when it came time to hand it off to Tyson so he could light the pink candle on the top while singing “Happy Birthday,” her father barged in and grabbed it straight from Lenny.

As Tyson sat parked in his truck, he saw a cop car nose out of an alley onto Smith Street and turn in his direction, moving slowly. He recognized the officer, a man who’d given him trouble in the past, by pulling him over for nothing—just to “chat”—no doubt aware of Tyson’s tainted status as a level-six offender. Though his stint at Youth Horizons had automatically wiped his record when he’d turned 18 last winter, the authorities seemed determined to toy with him, perhaps still angry about the stir he’d caused by making the bomb threat in a foreign accent. They’d tracked him to his aunt’s within 10 minutes, panicking neighbors up and down the block by thundering in in an armored SUV, wearing black paramilitary-style jumpsuits and brandishing laser-scoped long guns, not stubby sidearms. His aunt, unaware of the sneaky call he’d placed, was docked with her mobile dialysis machine when the authorities burst through the door. She fainted in her lounge chair. Tyson, fresh from the shower and wrapped in a towel, was handcuffed in minus seven seconds, his shoulders cranked back in their sockets, about to pop. Worse, the towel had fallen to his ankles and the commotion had made his penis hard, a condition he tried to will away but couldn’t.

Finding work after all that had not been simple. He didn’t want to have to search again.

The police car rolled past and Tyson drove away, obeying the speed limit, signaling his turns. He entered Kylee’s subdivision, a hive of noodle-shaped streets and cul-de-sacs lined by desert-tan three-story houses whose residents couldn’t cover their basic monthlies, forcing a lot of them to rent rooms to strangers. Kylee lived in a basement whose owner had set it up as a huge media room originally, with sectional sofas and a vast TV that covered one wall like a window into hell. Tyson found her there watching a movie with little Taylor, who was standing enclosed in a waist-high plastic cart that scooted around on gritty, scratchy wheels and featured various toys on springy stalks, including a dangling yellow microphone. The gadget worked. It amplified his voice, filling the room with booming babbles that Kylee, a nervous type, guiltily interpreted as orders.

“I’m getting your Cheerios. Promise. Hang on,” she said.

Tyson said, “Go do your laundry. Let me have him.” His theory of Taylor was that his talk was nonsense, just bubbles of sound-feeling bursting in the air, meaning Kylee was scrambling his progress toward working speech by attaching specific rewards to random blabs.

“He’s trying to tell us he wants a snack,” said Kylee.

“He’s got a snack. What’s that?” Tyson pointed to the gray bologna strips strewn on a tray clipped onto the cart. “He’s fine. Do your wash. We’re going to read a book.”

“He tore all the pages out. He wrecked his book.”

“Kids need multiple books. That’s pathetic. One book? That’s wrong.”

“We live a sad life in our enormous basement,” Kylee said.

“I’ll make up a story for him. Go away.” This was why he hadn’t moved away to work in Salt Lake or Las Vegas, the way his friends had. There was a mind at stake. A tiny mind.

The story he told tumbled out already formed, a tale of deception and enchantment that must have been a product of his fast, since nothing about it seemed to come from him; he wondered if he’d seen it in a movie or had it read to him by a babysitter, perhaps that old Basque lady who’d nursed his aunt. The setting was a gloomy mountain cavern, the throne room of a lonesome queen who’d plucked out her own eyes as a young maiden after glimpsing the man she loved kissing her lovely sister. In her court were two elves that competed for her favor by fashioning elaborate jeweled crowns whose beauty the queen could only take on faith, by listening to the elves’ descriptions of them. The cleverer elf, who was also the lazy one, eventually realized that the crowns themselves—whose brilliant gemstones could be obtained only by digging in a deep mine—were unimportant compared to the fine words required to rouse the queen’s imagination. Instead of toiling in the far-off mine, he crafted his crowns from homely pebbles and fixed his attention on learning fancy speech. This trickery enraged the second elf. He responded by digging deeper into the mine in search of brighter, larger gems, which he described to the queen in honest terms, along with the splendid crowns he made from them. This contest went on for many years, the clever elf growing grander in his language, the simple elf weakening from his taxing labors. Finally, on her deathbed, the queen announced that her kingdom would pass to the greater of the two craftsman, but rather than judge the matter herself, she would call upon her chief wizard, whose eyes were keen, to rank their workmanship. The simple elf rejoiced on hearing this, confident in his achievements, while the clever elf panicked, and, fearing the wizard’s approach, raised his fists and beat the simple elf.

“A curse on you!” came the voice of the wise wizard, who’d witnessed the conflict while floating in the air. “You need not have slain the poor creature, for you, my elf, were truly the best jeweler. Your rival turned rubies into crowns, but you, with your tongue, turned gravel into rubies.”

Tyson’s nephew, hot and small and damp, had curled up against him and gone to sleep. Tyson realized he’d told the story with his eyes closed, bobbing along in a cloudy purple dreamscape. When he opened his eyes and reentered the hard world, he smelled a pizza baking, cheese and sausage, and a spike of pure animal hunger drenched his mouth. He could eat now; the fast had succeeded. He’d broken through. He knew what to do. Not precisely, not in detail, but as a direction, a course across a map.

“If you’d just asked me, dummy,” Kylee said after he’d presented his ideas, “I would have told you the same thing. The way you describe it, it’s your only move.”

But a vision was so much better than advice.

According to the videos and websites that Tyson studied after work that week, gaining control of a woman, seducing her, had little to do with gentleness and kindness. Though women admired these qualities in theory, their real-life behavior, true pickup artists knew, revealed a preference for boastful, taunting jerks. Attractiveness? Also not essential. What mattered was keeping her doubtful and off-balance. What worked was leverage, and what was leverage? Fear.

Tyson’s first move with Mrs. Huggard was to start calling her “Carol” around the shop. She didn’t correct him, though he could see it rocked her; her hands went right to her body every time, smoothing her shirt or the hips of her brown slacks. The name seemed to put them on a different footing, elevating his and dropping hers, even, in some way, narrowing their age gap. She was 40, give or take a year. Tyson learned this by turning off the soft-rock radio station that played during work hours, per her standing order, and turning to an urban station. “They’re depressing, those 1960s songs,” he said. “All that high warbling makes me want to die. Sorry you had to grow up with that.”

“I didn’t. That last song—performed by the gifted Whitney Houston, if pop culture history interests you at all—was the number one hit in 1993, my senior year in high school.”

“Back in some farm state, you told me. Indiana?”

“Go Hoosiers!” Lenny barked, idling off to the side near the steel sink. His updated customer-service software plug-in cross-referenced the names of states and cities with a list of pro and college sports teams. Tourists loved it. They couldn’t get enough. They ran down long rosters of places, testing him.

“Minnesota,” Mrs. Huggard said.

“Go Twins! Go Vikings!”

“Question for you, Carol,” Tyson said. “And I need you to answer it honestly. And think.” He was leaning against the freezer, ankles crossed, his thumbs hooked inside the cloth belt that cinched his apron. His shirtsleeves, which he’d always worn down to hide the muddy amateur tattoo he’d given himself at Youth Horizons (Scorpio the scorpion, his sun sign, inside a ring of fire), were pushed up as far as they’d go, around his biceps. More skin showed inside his open collar, which also revealed a nickel chain formed from hammered, medieval-looking links. He’d bought it at a fair but never worn it, concerned that it might draw attention to the war zone of pitted pink scars on his throat and lower jaw. The pickup videos allayed this qualm. Concealing your flaws was a weak, evasive move that conveyed degraded mating status to the primal female brain. The power move, which required a rewiring of the shame-warped modern male nervous system, was to showcase your flaws, to stick them right up front.

“If I’m buying my girlfriend a hot new dress—on sale; that’s important, a dress I can’t take back—but I don’t know her size and I don’t want to ask her because asking would ruin the surprise, should I estimate down and risk buying one too small—if I do, I’ve blown a ton of money; it might be a sale dress but it’s still not cheap—or, to be safe, do I buy a larger size?”

“Except you don’t have a girlfriend,” said Mrs. Huggard. “Or has that changed? It might explain some things.”

“The question is purely hypothetical.”

“Let’s pray I caught it all. It stretched a little.”

“I’ll gladly repeat it.”

“Hush. I’m concentrating.”

“I hope you’re storing this, Lenny,” Tyson said. “This might be your first true insight into Carol. That question I asked her, you’re going to see, is like an X-ray of her personality.” Tyson was improvising here, patching a crack in his routine. In the video lessons, the model pickup artist had a buddy, a so-called wingman, who pumped up his image and created drama. He might mention that they were late for a cool party, say, or whisper to the target woman that the pickup artist’s desperate ex was lurking across the room.

“Too small,” Mrs. Huggard said. She seemed distracted; she kept casting glances at the office door where she’d been headed when Tyson waylaid her. Or perhaps she was miffed that a mother with plump twin boys had paused at the window just then and peered inside—intently, with her hands shading her eyes—and then moved along in the way some parents did when they couldn’t immediately spot the magical mechanized server they’d heard about.

“That tells me a lot about you. ‘Too small,’” said Tyson, determined to play out the whole bit. It had taken him almost two hours to memorize because it called for different lines depending not only on the woman’s answers but also on her posture and body language and whether she was alone or in a group. What’s more, the script’s potency wasn’t in the words so much as in the gazes, gestures, breaths, and other carefully planted hypnotic cues that led this woman, almost despite her will, to crave your attention and approval. Was it working on Carol? He'd soon see.

“What it tells me,” he said, “is that you’re vain. You worry about your looks, your weight, your shape. It also tells me you hope I like your shape. As my imaginary girlfriend, a role you unconsciously fell into there, you’re eager for me, your imaginary boyfriend, to perceive you as slim and trim. You’d be crushed if I bought the larger size. You’d fear I thought that you were fat, particularly if you are a little fat.”

“Brief time-out. Excuse me. People keep peeking in, then walking off.” Mrs. Huggard double-clapped her hands, the signal for Lenny’s motor to engage. “Command Reposition. Front window, center right,” she said. Lenny rolled toward his post with a high, thin, oiled purr. After a series of sensor-driven stutters and minute telescopic height adjustments, he stopped in a panel of sunlight and faced the street, his arms folded up at all three articulations, his claws retracted and fully sheathed.

“Go on. Your psychology test,” said Mrs. Huggard. She opened her stance some and cocked her head—good signs.

“That’s it. That’s all,” said Tyson. “Though I was thinking: After work some night, maybe I could stop by your apartment? To talk or whatever. Maybe watch a movie. You probably have great cable. I don’t have any.”

“A movie? At my place?”

“Or maybe not. Whatever. It was just an idea.” Error. Error. Once you’d leaned in, you didn’t lean back. You either withdrew all interest, baffling her, or leaned in further, going for the close. His eyes floated down to his shoes, another lapse, then wandered over to Lenny, so still, so solemn. Between tasks, between customers, he barely existed. Sometimes it was hard to remember he was the enemy.

“We could do it tonight if you’re free. And up to it.” Mrs. Huggard had opened her stance up even further, and soon, if the guidelines were correct, she would touch her neck or breastbone. There: the breastbone. Tyson felt rushed. They’d skipped a step somehow, he wasn’t sure which one, but the websites were clear: He should square his shoulders now and slacken his mouth a bit.

“If my friend is in town, I’ll grab a little weed,” said Mrs. Huggard.

“This just got interesting.”

“It always was. You just never seemed to notice.”

The TV set, mounted on a wall, was small for this decade and miles from the couch, so they sat on a checked red blanket, picnic style, and watched the movie from the floor. She mixed cocktails in an empty saucepan and served them in mismatched stoneware mugs. He noticed her kitchen was pitifully equipped and that there was not a plant in the whole place, just a sand-filled clay flowerpot on a low bookcase with three foil pinwheels standing in the sand. She chain-smoked menthol cigarettes. The clouds she blew caught beams of blue TV-light as she talked back to the movie, guessing characters’ lines before they spoke them, ridiculing weak points in the plot and specifying the camera shots (“Zoom in,” “Track back,” “Fade out”). Her ashtray was a Coke can with Coke in it; lit butts inserted in the hole hissed and sizzled. She said money belonged in the bank, not in the house. She voted Republican, thought Democratic, and lived Libertarian, she said, and then she explained what this meant; he didn’t know politics. Their first physical contact was when she slapped his thigh, playfully but with stinging force, during a courtship scene she found absurd because the woman didn’t seem to mind being pushed down by the man into a snowbank. He caught inklings of Mrs. Huggard, bursts of Carol, and waves of a third being who contained them both and seemed to have whirled up out of a brass lamp. She wore gym shorts, a green, spangled blouse thing and no bra, her breasts bobbed like rubber bath toys. That she’d chosen to dwell and do business among Mormons made no sense to him, although maybe she lived for close getaways, quick changes. She apologized for not finding any weed but said she’d brewed tea from cloves and magic mushrooms and spiked it with lemon vodka to make their drinks.

“So why this weird new you?” she said. “All shitty and cute and party with the boss?”

“I’m not sure I know. I’m 18. I try things out.”

“When I was 18 things tried me out.”

“Do you mean guys?”

“More like forces. Approaches. Ideas. Schools of thought.” She drank some spiked tea and then peered into her cup as though she’d spotted a bug, a hair, her fortune. “You’re right, though. They usually took the form of guys.”

They sat. Nothing happened. They were just together. She poked a butt into the Coke can hole and up came a twisty braid of silver smoke that she blew on, separating it into strands. Her hair, with the spray gone, fell straight and smelled like pencils. He wanted to thrill her, suspecting few ever had. He didn’t care about her thrilling him because calming down enough for that to happen seemed impossible tonight.

They sat on the bed beneath the cowboy poster, unzipping and unhooking. She took the lead but then he took it back, pushing her down. “You have instincts. Good,” she said. He kneed her legs apart and used his hand on her, though possibly too scientifically at first, because she soon took control of it with her hand and moved it more crudely, with over twice the pressure, which made him feel rebuked. He bent down to kiss her but she turned her head, so he chewed on her ear. She seemed unmoved. She lifted his hand off and said, “We had a rhythm there but now it’s like we’re scrubbing a pot. Plan B.” He interpreted this as a request to use his mouth, and indeed she reached behind his head and dug her nails into his scalp and drew him down. But not all the way down, as though she’d reconsidered or detected a need to use the bathroom first. He went ahead anyway. Progress. Her motions started. The energy rose for a minute but then it leveled, and then he felt it running off somewhere—water overflowing from a sink. Her hand left his head and he felt her body torque. Glancing up, he saw her stretch an arm out and reach behind some books stacked on her nightstand. He resumed his task.

He heard a whining noise, a high-speed grinding. It was steady at first but then turned choppy, pulsing. Between his lips and the surface he imagined as a melting scoop of French vanilla, something rigid intruded. It thrummed and buzzed.

“Stay down there. Be partners. Work with it,” she said. “This isn’t either-or. I want you both.”

The vibrator bumped his cheekbone, chattering his jaw. He moved his mouth aside to give it territory but it kept advancing and claiming more. Soon, the widening of time produced by the boozy mushroom tea became a scriptural chasm of agonies. Snapping to for a moment, he perceived that he was contributing nothing to the effort now—the locust invader had cast him to the side—yet she still seemed to want him down there, on her team. Teamwork. At Youth Horizons, it was everything. A man without a team, the program taught, was weak and doomed and to be pitied, but a young man alone was to be feared; he tended to grow into a menace. So get with it. Keep at it. Hum along. This droning misery can’t go on forever. On Sunday mornings, certain hymns seemed endless, but then he’d turn the page and see that there was only one more verse. Knowing this, he sang more powerfully. Everyone did. They sang for their release.

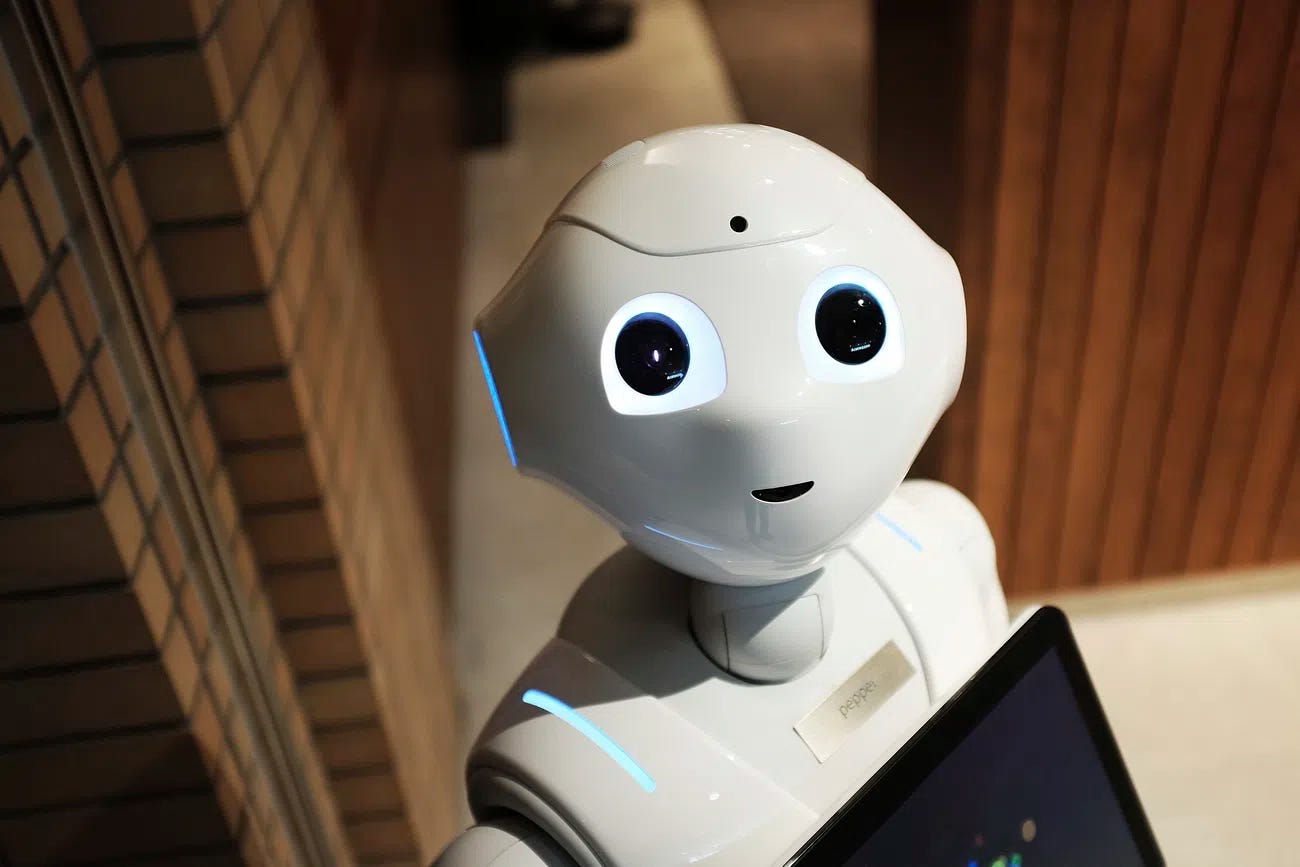

“I scream, you scream,” Lenny chants to the kids, who chant along with him as he moves his arms. He learned this by copying the boy. Then the boy stopped doing it. This is also what happened with the bananas. Lenny could slice them crosswise from the start, but only the boy knew how to slice them lengthwise. Then one day Lenny did it: banana halves. The boy took the knife away and put it somewhere. Then the boy left too. Lenny began practicing with a smaller knife. He sliced bananas into halves, then he learned to slice them into thirds, and then to shave them thin: banana curls. He learned on his own, by himself, without his teacher.

The cherry boy.

“We all scream for ice cream!”

I'm ashamed to say I've never read any of Walters prose, only articles and commentary.

I see now why he's so popular.

the dude can write...

Boy this story played a lot of notes in my mind. Memories and images and thoughts of my own somewhat misspent youth. But I think the cherries are important too, so maybe we need humans after all. Thanks Walter.